My Neighbor Totoro in 196,883 Dimensions

I often think this world is all too random, even though in many cases it seems so fine-tuned. It would be too cliché to say that the truth is somewhere in the middle. Maybe that’s just how it is, though, and it’s not worth asking any further. One branch of mathematics has essentially reached this conclusion, which unfortunately just makes me want to know why that is. Especially for the Monster.

All the sources I’ve encountered say that one of the greatest achievements of 20th century mathematics is the classification of the “finite simple groups.” An intriguing, yet also frustrating, aspect of math to me is that it uses its own peculiar language. I understand each of the words in that phrase individually, but in math it means something very specific that doesn’t align with everyday uses of those words. We have to start with the last word here– group– to get at the root of this.

Let’s say you’re quite tall and looking down at a square table below you (or you’re quite short, and you’re looking down at an even shorter table). You want to rotate this table so that it will still look like how you see it right now in this starting position. Out of all the permutations you try– and you try all of them– there are exactly four that result in it looking like its original shape.

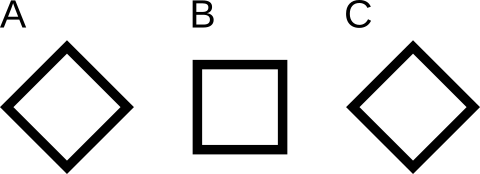

You’re looking down at the table as in (A), seeing a diamond shape. Rotating it 45 degrees clockwise yields a square shape (B), whereas 90 degrees produces the same diamond shape (C). You can repeat this rotation 3 times, for 4 times total.

You’re looking down at the table as in (A), seeing a diamond shape. Rotating it 45 degrees clockwise yields a square shape (B), whereas 90 degrees produces the same diamond shape (C). You can repeat this rotation 3 times, for 4 times total.

This is known as maintaining symmetry, where “symmetry” here in math means the same as in regular language. The collection of these movements that yield a symmetry is known as a “group.” Thus, a mathematical group contains the ways to preserve symmetry of a shape. The group for our table has a specific name (C4), and the features of this group apply universally, for all mathematical objects that have the same types of symmetries as our table.1 I’ll conclude by clarifying that groups do not describe all the different shapes that can possibly exist: they instead describe all the ways in which configurations of points can be different.2 When mathematicians in the 20th century completed the classification of finite simple groups, it means that they mapped out the underlying structure of all symmetries.

Stated differently, the finite simple groups are like the elements in the periodic table, except for mathematical objects instead of chemicals and molecules.

I know it’s still abstract, but once it clicks, it becomes more engaging. Instead of covering the basic implications, I want to skip ahead to the very final point, which may feel a bit like jumping to end of a complex novel, yet also seems necessary to capture just what the Monster is.

While our square table, which exists in 3 dimensions, has 4 symmetries, the Monster moves in 196,883 dimensions, and has 808,017,424,794,512,875,886,459,904,961,710,757,005,754,368,000,000,000 symmetries.

Which, you know, is about 8 * 1053 symmetries.

Yes, this is the largest group, and no, it’s not known why there is nothing bigger. Although it seems arbitrary, it almost certainly can’t be arbitrary, because there’s too many coincidences about it that align profoundly with seemingly unrelated areas of mathematics, such as number theory, modular forms, and string theory.3 As of this writing, there is not a single compelling reason for why it’s there, or why such synchronicity arises across disparate branches of math.4 This situation with the Monster is like finding a new element that doesn’t fit into the periodic table that’s as large as all of the other elements combined, times septendecillion.

My hunch is that somewhere out there, Totoro is grinning in 196,883 dimensions, totally aware of what he’s up to.

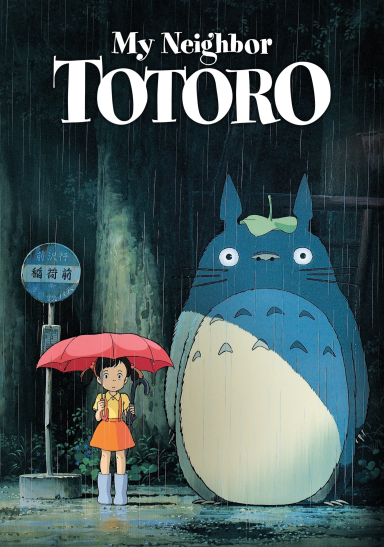

Cover art for the English-language release of the 1988 anime.

My favorite takeaway from the Studio Ghibli film My Neighbor Totoro, which depicts an anxious 10 year-old girl named Satsuki encountering a mystical woodland creature known as Totoro, is that Totoro also likes exploring Satsuki’s world. While he enjoys showing Satsuki parts of his spiritual forest, he genuinely finds satisfaction in witnessing the effect he can have on Satsuki by empowering her to gain self-confidence and become a stronger, braver individual. Satsuki’s human world is new to Totoro too, and he becomes a part of it by accompanying her on her journey of growth and discovery. Totoro relishes knowing more than Satsuki, and he recognizes that simple words of encouragement would just fall flat; he has to show Satsuki her own potential in order for her to fly higher.

Totoro’s path through life wouldn’t be the same if he weren’t able to fully connect with Satsuki, though. It’s through their joint expeditions that they each can find and create meaning for the otherwise unclear parts of their lives. For Satsuki, she’s able to resolve the tension of her anxiety around her mother’s illness; for Totoro, he’s able to ground himself in an existence with real consequences beyond aimlessly wandering around illusive playscapes all day. Without each other, Satsuki and Totoro each are a little lost; together, they’re able to locate their paths forward.

The Monster appears to represent the maximal way to apply symmetries in a unique way not covered by any other group. To paraphrase the late mathematician John Conway again, the Monster is like a particular snowflake Christmas ornament, with its own shape not seen anywhere else across the mathematical landscape. This snowflake somehow is the basic building block for a mathematical phenomenon that depends on it, just like life on Earth depends on carbon bonding with other elements. As with Totoro’s forest world, the Monster indicates that the world of mathematics is so much larger than we can currently imagine. By exploring this world as Satsuki does with Totoro, we can gain a new perspective for both the meaning of the abstract world and our physical world.

It’s humbling to write about the finite simple groups at this precise moment, and for you to read it, when there’s no understanding of why the Monster is there. For most of human history, people did not know (or at least did not accept) that the Earth revolves around the Sun. I don’t know if the Monster’s role will prove to be as consequential as the calculations that led to theories of gravity and ultimately to the nature of space and time itself. Still, I find it hard to imagine that our 196,883-dimensional Totoro has no connection to us. In the movie, Totoro appears to Satsuki in a time of need. What will our need for the Monster be? I’m as unaware as everyone else, but knowing that it’s there is enough to keep me gazing at the stars.

Your readership is more than enough. Still, if you’d like to buy me a coffee, it’s the clearest signal to keep writing.

Footnotes

This explanation with the table is what Edward Frenkel uses in his book Love and Math. Highly recommend.↩︎

This line is from Grant Sanderson’s 3Blue1Brown video “Group theory, abstraction, and the 196,883-dimensional monster”.↩︎

Check out “monstrous moonshine.”↩︎

I’m taking the words at face value from two people deeply involved in the Monster, John Conway and Richard Borcherds.↩︎