6 Dance with the Dark

I never thought I would read Carl Jung. He’s a footnote in psychology, right? A historical figure around the time of Freud, who had a bunch of non-falsifiable theories about the psyche, dreams, and things like that? That was pretty much how Jung was introduced every time I encountered him in neuroscience contexts. From a data-driven, biomedical perspective, it’s not an entirely inaccurate characterization. Since Jung was born in 1875, though, we shouldn’t expect him to have a mechanistic understanding of the nervous system, which didn’t really form until decades later.

That, for me, was when it clicked: when I realized that Jung works at a level of abstraction above the nervous system. He’s not describing the brain, like how a researcher might try to uncover neural circuits that mediate social behaviors. Jung’s attempting to address the mind, the world of our conscious and unconscious thought. Believe me, though, I am not a dualist: I don’t think that the mind is something separate from the brain.

Yet, I do think that what we experience, our moment-to-moment embodiment of reality, cannot be reduced to something like the activity of a brain region, or the presence of a neurotransmitter, or a change in gene expression. Sure, those mechanisms may ultimately lead to a particular behavioral output, but they don’t explain what it feels like as that behavior occurs to the conscious entity. And how could it? Until there’s a way to de-encrypt every single possible neural recording at every single moment, as if reading sheet music, we don’t truly know the source code inside our heads. That leaves a lot of room to think about what may be going on.

In modern terms, Jung was a therapist. He may have had a medical degree and practiced as a psychiatrist, but he didn’t prescribe medications. His goal was to help clients cope with troubles in their lives through dialogue. In my reading of Jung, his attempt to treat what he called “neuroses”– only some of which today would be considered mental illness– opens an entirely new window to understand our consciousness, whether he intended that or not. Applying Jung’s approach has proven inspirational to me in many areas beyond mental health, ranging from creativity and artistic analysis to interpersonal relationships and individual development.

Unfortunately, in order for Jung to really resonate with me, I had to first enter into a rather dark place, which Jung then helped me through. Some part of me wonders, of course, if I just fooled myself as a way to ease the pain. I want to use this essay as a chance to highlight why I find Jung’s framework so appealing, and why I think others may benefit from appreciating his thought more, without first needing to face what I faced.

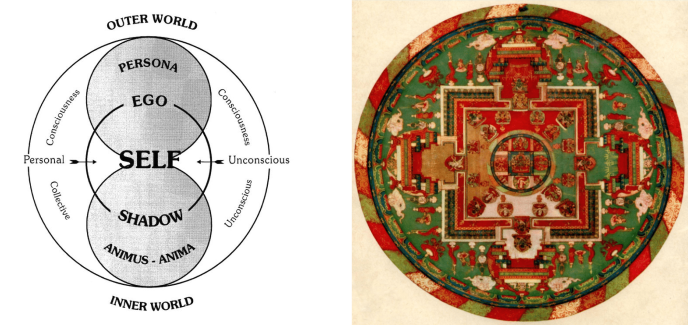

Jung’s structure of the psyche hinges on the balance of opposing forces, directly inspired by the circular mandalas of Eastern religions and philosophies (as shown here on the right of his cover for Man and His Symbols from 1964.) Note that diagrams like the one on the left are not made by Jung himself, instead coming from decidedly non-scientific sources like The Middle Pillar: The Balance between Mind and Magic by Israel Regardie.

To begin, it has to be emphasized that Jung did emerge as an admirer of Freud, and the two communicated closely for many years. They eventually came into a professional and personal split, resulting in two distinct approaches: “psychoanalysis” for Freud, and “analytical psychology” for Jung. This is not just psychoanalysis plus some extra stuff; Jung’s conception of the mind fundamentally differs from Freud’s, and therefore draws non-reconcilable conclusions.

The opening of Two Essays on Analytical Psychology (1928-1943) introduces what sets Jung’s vision apart. He explains that when counseling a patient with neurosis, Freud’s method would identify the source as a form of sexual repression. However, some alternative approaches did emerge, such as from Alfred Adler, who developed his own school with power differentials as truly underlying neurosis. Jung could carry on with other methods, but he stops here, asking now: how could two different views, each claiming absolute certainty in opposing domains, both be correct?

If a theory of sexual repression helped some patients, and a theory of power differentials helped another, Jung supposes that each theory may instead be capturing a subset of a broader theory of the mind– something akin to the “theory of everything” that still eludes physics. Where Freud and Adler go astray, Jung claims, is that each points to the wrong single cause for what underlies neurosis. Triumphantly, Jung declares that the true cause is not something about merely sex or power, but about an imbalance of the self.

I know– that sounds so wishy-washy and nondescript as to be meaningless, and I think it’s why Jung’s work became associated with hippie spirituality rather than anything scientific. While what I’m about to describe still wouldn’t pass in any peer-reviewed journal, I think if you take it for what Jung used it as– practical advice to aid the struggling individual– there can be great utility, even if it’s not exactly quantifiable.

Jung’s central concept of the mind revolves around balance, supposing that our consciousness emerges from the unity of opposing forces. An imbalance in any area can lead to dysfunction somewhere else. Crucially– and this can be the hardest part to accept– the space of our balanced mind encompasses our unconsciousness, of which we are unaware. Unlike Freud, who claims that the unconscious constantly strives to dominate over regular consciousness, thus creating neurotic tension, Jung observes that the unconscious instead provides a window to information we otherwise wouldn’t access. This is best illustrated to me by Jung’s idea of the “shadow”:

… A dim premonition tells us that we cannot be whole without this negative side, that we have a body which, like all bodies, casts a shadow, and that if we deny this body we cease to be three-dimensional and become flat and without substance.

In this framework, our internal fears, doubts, frustrations, angers– the emotions that torment us– are reflections of our shadow selves, the parts of us that reveal our vulnerabilities. Just as our conscious selves are not one static thing, but a process, our shadow selves evolve alongside our conscious selves.

The exploration of this dynamic, between self and shadow, culminates in what Jung terms individuation– the mind’s integration of the unconscious into the self. Rather than being ignored or avoided, the weaknesses and anxieties revealed in our shadows are to be understood so that that we may incorporate them and become stronger. Individuation acts as a mirror between our incomplete and whole selves, enabling us to use the past to build a better future. Or, as Jung said:

… Life does not have only a yesterday, nor is it explained by reducing today to yesterday. Life has also a tomorrow, and today is understood only when we can add to our knowledge of what was yesterday the beginnings of tomorrow.

If this sounds a lot like Taoism, that’s not an accident; individuation in analytical psychology is very much “the way” of Taoism. Both philosophies are fundamentally relational, centered around the connections between concepts, rather than the essences of the concepts themselves.

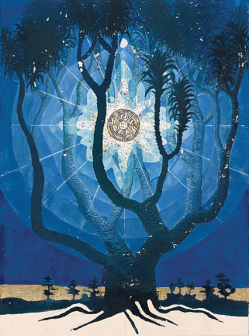

Jung’s own artwork, best collected in The Red Book, often captures dreamlike scenes emphasizing journey and discovery as felt during individuation.

A quick glance on Wikipedia will list many other Jungian terms that I didn’t mention– archetypes, persona, animus and anima, collective unconscious– and your mileage may vary with any or all of those. As characters in a story, I quite like them. Yet for me, seeing my shadow was enough. I found that it’s not about shining a light to erase the darkness around you. It’s about learning to move forward with only your candle, as the shadows flicker endlessly, to a place you haven’t been before, a place that challenges you.

Yes, I’m scared. I’ve also never felt so ready for this dance with the dark.