11 A Complete Identity for Psychology

If light itself can bend due to gravity, we should forgive ourselves for swaying in the wind. Then why do I often feel guilty for falling when the wind is strongest? Rather than crediting the objective, physical force around me, I find it easier to blame my own non-quantifiable weakness. It’d be scarier to admit that there are things I couldn’t face.

Something about a particular scene in Martin Scorsese’s 1976 film Taxi Driver channels this notion in a different way. A cab driver nicknamed Wizard says in a moment of mentorship to Travis Bickle:1

You choose a certain way of life. You live it. It becomes what you are. I’ve been a hack 27 years, the last ten at night. Still don’t own my own cab. I guess that’s the way I want it. You see, that must be what I am. … Look, a person does a certain thing and that’s all there is to it. It becomes what he is.

Perhaps since it’s easier to flatten than to construct, we like to define each other by what we do. (At least in the US.) Work isn’t just a common topic of small-talk for adults; grown-ups also ask children what they want to do when they grow up, and furthermore, what they want to be. Such a question implies a link between action and identity. While it makes sense to a degree, I’m not sure this link always holds. There can be great liberation separating doing and being. What does it mean, then, for psychology to be the study of the mind and behavior, if what it does is often far removed from that?

A friend recently recommended to me “On Becoming a Person” by Carl Rogers, a collection of essays from a founding practitioner of a branch of psychotherapy centered around holistic understandings of individuals. The book carries strong echoes of Taoism and Carl Jung, and I came upon a unifying reveal in Chapter 6, when Rogers writes about his observations of successful outcomes from therapy:

What kind of a person does he become? … The individual becomes more open to his experience… It is the opposite of defensiveness… We cannot see all that our senses report, but only the things which fit the picture we have. This defensiveness or rigidity, tends to be replaced by an increasing openness to experience… He is able to take in the evidence in a new situation, as it is, rather than distorting it to fit a pattern which he already holds.

Rogers often describes patients who struggle at first to cope with their own emotions, and then gain the strength to carry forward upon recognizing their own limitations. This initial defensiveness stems not from some mystic mechanism of the psyche but rather our own default resistance to change. For individual development, growth emerges from the interaction between inner experience and outer events. This isn’t something that can be explained by altered gene expression, or different concentrations of neurotransmitters. It’s something that’s encountered and confronted.

Reading Rogers has helped me realize that psychology, beyond being an investigation of the brain and consciousness, can be more completely understood as the experiential dynamics of change. My entire scientific training in neuroscience, which from the beginning occurred across biology and psychology departments, focused exclusively on a mechanistic, molecular framework. Since its inception, however, psychology has sat somewhere between philosophical, scientific, clinical, and even spiritual modes of inquiry. Although I understand why from a biomedical and technological point of view you’d want to focus on the aspects of the brain that you can quantify, the parts without any ambiguity, the turn towards reductionism is comparatively recent.

Perhaps it’s precisely the ambiguity that make psychology shine, though. It needn’t be a flaw that the topic can be approached through all of experimentation, literature, art, medicine, and meditation– this breadth can be its strength. If physics and chemistry happen in calculations and test tubes, psychology happens at the interface of our selves with the world, a messy amalgamation of individuals engaging the universal wielding only emotions, fears, and curiosity.

Psychology lacking an impartial, formulaic foundation does enable questionable prophets and gurus to mislead. Yet embracing its texture, its uncertainty, can also provide a worthwhile path to share with the right guide. If the fundamental theorem of calculus neatly summarizes the mathematics of change, the human condition isn’t so succinct. Let neuroscience, psychiatry, neurology, and cognitive science tackle the details of neural functioning– psychology will fill in the gaps.

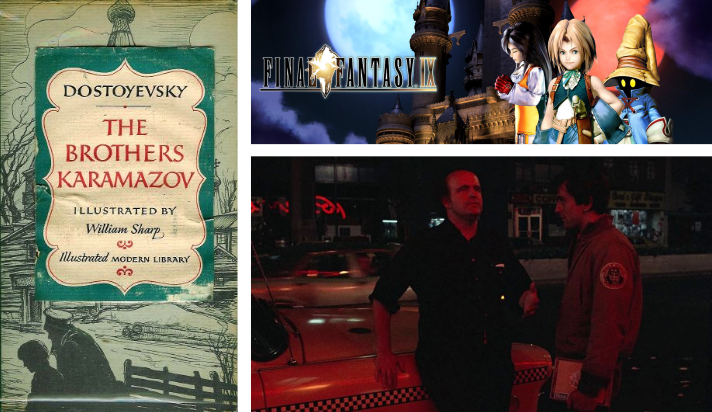

The novel The Brothers Karamazov (left), the video game Final Fantasy IX (top right), and the film Taxi Driver (bottom right) all explore identity, meaning, and purpose from the perspectives of the individuals navigating those worlds. These themes are psychological, not only philosophical or literary, because we respond to changes in the works as we experience them alongside the protagonists.2