8 Reality’s True Representation

Quantum mechanics is full of so many quirks (and quarks) that it makes reality seem like a game, where all of us are players on a strange board. In this universe, a coin can be both heads and tails in superposition, and particles can share entangled properties that affect one another instantly no matter how far apart they are. With outcomes like these, how are we supposed to even know what “real” means?

Observing reality from our vantage point comes with as many advantages as it does disadvantages. We can be sure of our own observations and experiences, however limited they may be in revealing the nature of truth. We can trust math to the extent that we grasp it, until it becomes a foreign language outside the bounds of understanding. The attempt to bridge these two approaches, personal interpretation and abstract logic, may just hold the key for translating the meaningless into the meaningful.

I found an interview recorded in 2014 with Greg Ball, an influential neuroscientist who happened to train my doctoral advisor, where he makes the following comment about the style of research done during his time in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Johns Hopkins University:1

You do experiments, you collect data, you analyze the data, you don’t sit and make up big bullshit theories and all that kind of stuff, you experiment, experiment, experiment.

He then explains that the separate Department of Cognitive Science formed in response to this attitude disregarding theory, so that there would be a space for abstract model-building less constrained by empirical results. Throughout the interview, Ball does not outright dismiss theorists or hold up empiricists like himself as inherently better; he’s only describing the particular tradition within his department. Perhaps this is why the following passage stuck out to me when I came across it in a separate talk by him, recorded in 2016, saying this about the state of neuroscience:2

For me, the big question is what I call the “levels of analysis” question. We all know that the brain is responsible for cognitive and affective processes that regulate behavior. We’re past dualism. And we have the reductionist program that assumes if we can characterize neural processes in terms of DNA, gene expression, and epigenetics, we’ll have this fundamental answer on mechanisms to these governed brain processes. And there’s some great examples… But we’re not translating our levels of analysis among themselves… We can’t map these upon [each other]… What does it mean when you have a gene expression change, or morphology change for physiology, and then emergent properties of cognition in the brain?

His point here, despite extolling the merits of experimentation in the 2014 interview, illustrates that pure empiricism does have limitations: it alone can’t account for a holistic understanding of complex, emergent phenomena. Some model is needed to account for the integration across each level of analysis. Yet if the “bullshit theories” are relegated to a separate department, how is this model supposed to develop?

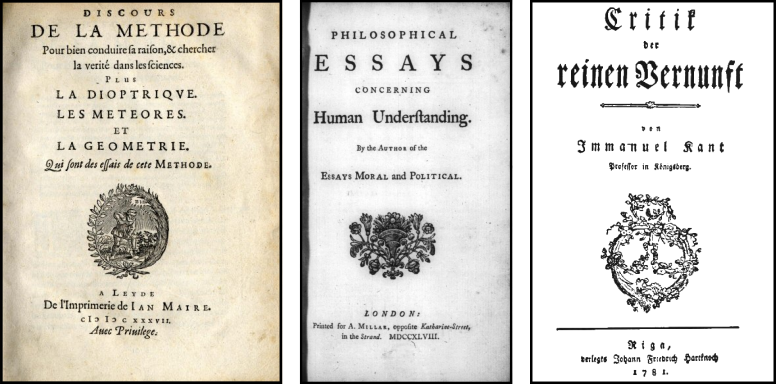

This topic isn’t new. Discourses favoring rationalism, empiricism, or some synthesis of the two have been going on in multiple languages since at least Descartes, Hume, and Kant (spanning 1596-1804).

I get where the frustration comes from– much of psychology and cognitive science seems too far removed from the underlying brain function to be falsifiable, and you quickly run into situations where people compete more on the strength of their prose and argumentation than experimental validation. I also resonate with the need for higher-level synthesis, because otherwise you get an opposite situation where laboratories produce data in silos with a lost plot.

David Marr, in my opinion, best resolves this conundrum in the first chapter of his 1982 book Vision, where he delineates information processing into three streams. The middle level, the representation of information, most closely relates to the neuroscience problem raised above. Marr illustrates multiple ways to represent numbers, such as with Arabic numerals (digits 0-9), binary numerals (digits 0-1), or Roman numerals (I, V, X, etc.). While the underlying mathematics doesn’t differ with the representation, the information conveyed does. The number 37 in Arabic numerals indicates that the digits are built from powers of 10, while the same amount written in binary (100101) reveals the use of powers of 2.3

Marr notes that any attempt to abstract information carries some trade-off coupled to its advantages. While the Arabic numerals are great for human mental arithmetic– and proved to be much more useful for calculations than Roman numerals– binary numerals work better in digital (or silicone) contexts. The information gained for one purpose leads to information loss for another.

I think this is the crux of the issue that concerns Ball. Neuroscience represented by rigorous experimentation produces quantifiable, replicable results in particular domains, at the expense of transfer across those domains. When represented by theoretical models, neuroscience can generate unifying, cross-domain explanations and predictions, though often with low resolution for any specific mechanism. With Marr’s framework in mind, these approaches shouldn’t be viewed in opposition, except for where the contradictions would be clarifying.

I bring this topic up because for this world we find ourselves in, we, as humans, are the representation of our particular consciousness. We all share the same nervous system fundamentals, from our cells, neurotransmitters, and circuits for things like learning and memory to language and our capacity for dreams. Our minds don’t exist in a vacuum; we arrive with a pre-formed architecture that grants us exceptional capabilities and also frequent blind spots. The experience of being human on Earth, with its endless highs and lows, clarity and contradiction, is how this particular form of consciousness exists, how this reality transmutes the unbounded into the quantum. There’s something to celebrate in that, even if the truth always feels a little out of reach.

Determination confronting the unknown in Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818) by Caspar David Friedrich.

https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/items/8fc3536f-478e-4572-b326-109418c94724↩︎

Shown below: - = (3 × 101) + (7 × 100) - = (3 × 10) + (7 × 1) - = 30 + 7 - = 37 - = 100101 - = (1 × 25) + (0 × 24) + (0 × 23) + (1 × 22) + (0 × 21) + (1 × 20) - = (1 × 32) + (0 × 16) + (0 × 8) + (1 × 4) + (0 × 2) + (1 × 1) - = 32 + 0 + 0 + 4 + 0 + 1 - = 37↩︎